The Open Data Scotland Conference organised by Holyrood magazine on 10th December was a landmark occasion, and the keynote talk was delivered by Rufus Pollock, founder of the Open Knowledge Foundation. We decided to capitalise on Rufus’s trip north by organising an impromptu #OpenDataEDB on the preceding day, giving him an opportunity to find out a bit more about what we’ve been up to, and giving us a real boost of inspirational energy. Rufus made a longer-than-lightning presentation in the first half, followed by four other talks that outlined exciting open data projects taking place in Scotland. Unfortunately the presentations by Gill Hamilton and Ally Tibbitt had to be postponed, but Clare Taylor and Steven Kay were generous enough to step up to the plate at a moment’s notice.

Following the example of #OpenDataGLA, we live-streamed the event, and the recordings can be found here:

Rufus Pollock: Introduction to the Open Knowledge Foundation

Rufus talked about the history, work and future of the Open Knowledge Foundation, and started off by showing a professionally produced 2-minute ‘promotional’ video that explained the significance of ‘open by default’ and the advantages of opening up knowledge. He explained that despite their name, the Open Knowledge Foundation initially had no endowment to fund their work, but just began by “doing stuff” with data and information, inspired by the example of the Free / Open Source Software movement. He argued that the real innovation of recent years is the small data revolution, not big data; that is, data that is accessible to individuals on devices like laptops and smartphones and that enables interaction and collaboration. So how can we use this data to empower ourselves?

The work of the Open Knowledge Foundation fits into three main areas:

- Defining what is meant by open data — ideas that were first developed by OKF in 2005 and have now gone mainstream.

- Since data by itself is not enough, OKF has been building tools (such as Where does my money go?) and disseminating skills that will allow ordinary citizens to turn data into insight.

- Creating communities and collaborations to use open data — “because together we do stuff!”

Related to Where does my money go? is Open Spending, which can be thought of as the OpenStreetMap of public money, mapping money worldwide. Two years ago, there was only data for a couple of countries; now that has expanded to about 55. Is Edinburgh’s budget there? Answer: not yet! (It doesn’t seem to be available in machine-readable form.)

Three to five years ago, most of the problem was that data wasn’t available. The Open Knowledge Foundation is now placing greater emphasis on making such data used and useful; this requires both tools and skills. One big project supported by the Open Knowledge Foundation is the School of Data, which teaches skills for finding and interpreting data, focusing on an audience of people who are not interested in open data. Data expeditions are intended for people who aren’t techies, but who want to ask a question and explore it in an engaging and interesting way.

Rufus emphasised the diversity of projects that the Open Knowledge Foundation is involved in, from cultural projects such the Public Domain Review and Open Literature to more technical initiatives such as CKAN, a “WordPress for data” now used by data.gov.uk, and OKFN Labs (“a working group for geeks”). He emphasised that most of the projects were initially just the passion of a single individual, and eventually gathered momentum and support from the wider community. A recent addition to the portfolio of projects is Philippe Plagnol’s Open Product Database, which goes beyond data that is available even within the industry, and connects up to Wikipedia pages on brands.

Moving forward he suggested that the breakthrough for open data will come when it becomes attractive to average people, average developers and average companies, just because it’s easier to use than the alternatives. A key challenge therefore is how to build a frictionless data ecosystem. Where published open data is of poor quality, there is often no way of sending feedback to the maintainer. What is needed is an issue tracker for data sets: not a method of making comments, but a facility for reporting problems and seeing whether they have been resolved. “We need a world where getting data, cleaning it up and sending back fixes, sharing your improvements and sharing your data generally, are all incredibly easy.”

Rufus also urged us to block out our diaries for next year’s OKFestival in Berlin, 15–18 July (“Berlin in July is a very nice place!”): it’s incredibly enjoyable and a fantastic opportunity to meet with people from across the spectrum of the international open knowledge community. Last but not least, OKFestival will be an opportunity to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Open Knowledge Foundation.

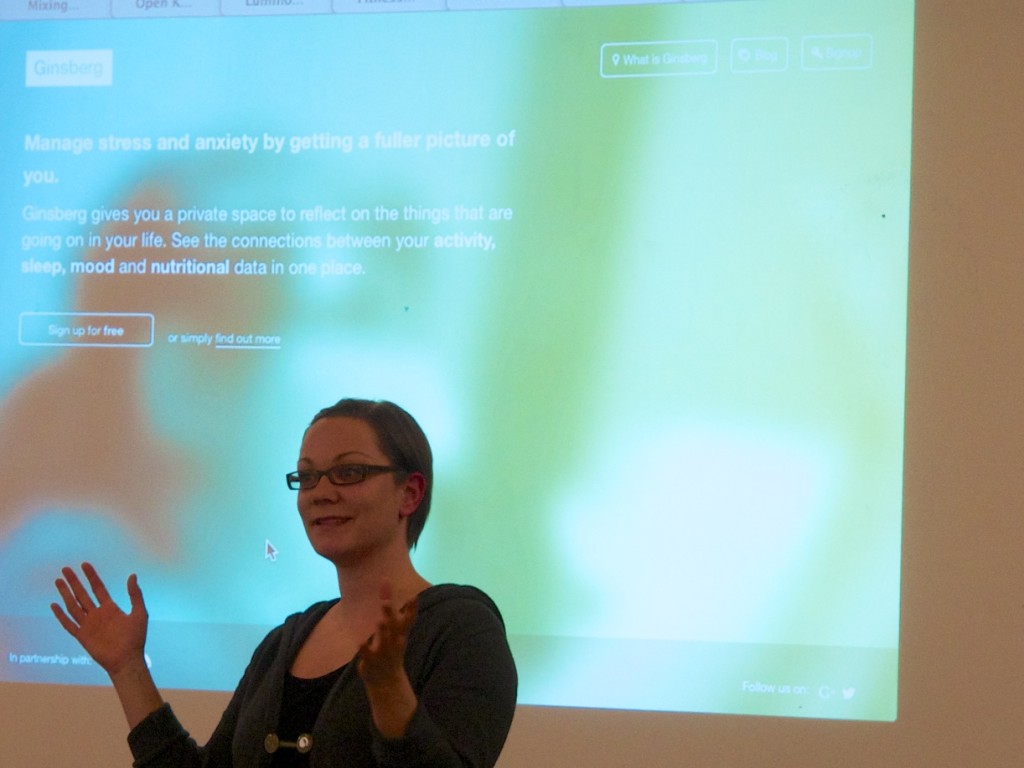

Leah Lockhart: Project Ginsberg

Leah gave us a quick introduction to Project Ginsberg, a joint initiative by Scottish Government, NHS 24 and New Media Scotland. It aims change policy and build new technologies that will improve mental health across Scotland. In the current phase, it is building a small suite of resources for that will enable people dealing with stress and anxiety to reflect on their personal objective and subjective data. Objective data will be collected via phone apps like RunKeeper and devices like Jawbone UP, while subjective data will be collected via the help of clinical questionnaires. By combining and presenting this data in a variety of ways, the project aims to help people see correlations between things that contribute to mental difficulties. The project hopes to give people insights about their behaviour, about what’s happening around them, a whole picture of their life.

An alpha version of the Ginsberg Dashboard will be released in a matter of weeks, and the project is keen to enrol volunteers who will give them feedback on the prototype.

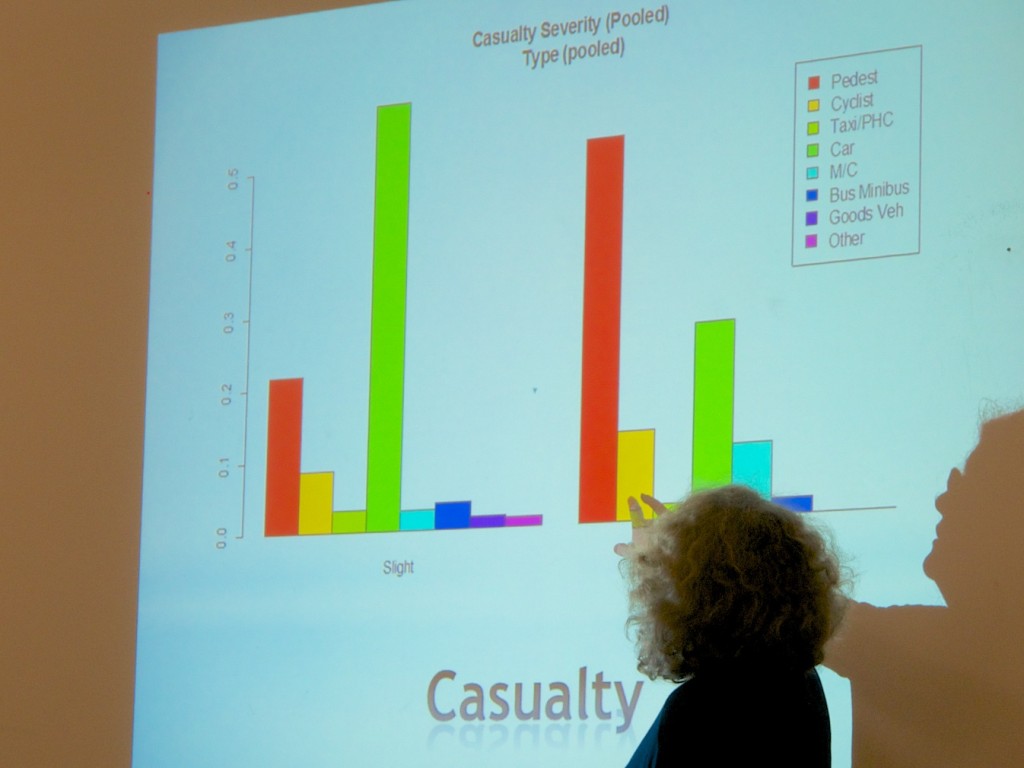

Clare Taylor: Glasgow Future Cities Project

Clare described her work within the Future Cities Demonstrator on finding and analysing data on road safety in Glasgow. Starting from the UK-wide Road accidents and safety statistics (STATS19) published as open data by the Department for Transport, she extracted the accident and casualty data that was specific to Glasgow Council. This of course make the data a lot more manageable for people without advanced data hacking skills. The accident data includes geographical and temporal coordinates, together with information about number of vehicles, type of road and so on. She noted, from the data about the gender of drivers, that while women might be crap at parking, they are awfully good at avoiding accidents!

Clare and her colleagues have used the geo-data to build maps of accidents and casualties in Glasgow that allow the accident and casualty information to be easily visualised. They also have an animation which shows how accidents spread and contract across the city in a 24 hour cycle. These will be made available shortly from the Glasgow Open Data site. There are also maps of the accidents in the Glasgow area that include information on the numbers of vehicles and casualties involved and the severity of the accident.

Clare noted that the geo-coded accident data complemented the local knowledge of citizens in intriguing ways. For example, it was well known in her part of the city that the point where a narrow, winding road joined a major road with heavy traffic was particularly tricky to negotiate; often, drivers would become impatient with waiting and would take dangerous risks in exiting the junction. This informal acquaintance with the situation was reinforced by the quantitative data, which showed unequivocally that the junction was an accident blackspot.

Tim Foster: Mapping Communities with OpenStreetMap

OpenStreetMap volunteer Tim Foster described how a weekend of mapping local data in Dunbar (part of the Sustaining Dunbar project) had allowed him to identify and visualise lots of different kind of information that was relevant to the community. This included an analysis of how the network of cycle paths could be improved by joining up currently disconnected segments, and how access to the railway station could be improved for an entire part of the town by the addition of one small but crucial footpath. This in turn could have significant implications for increasing uptake of public transport. Tim also showed how the data from mapping features could be used to extract interesting statistics about a locality; for example, although Dunbar has 1 hectare (approx 5 football pitches) of playgrounds, this is dwarfed by the 6 hectares (approx 37 football pitches) devoted to car parking.

There’s a longer version of Tim’s talk online and some related R code.

Steven Kay: Edinburgh Shop Local

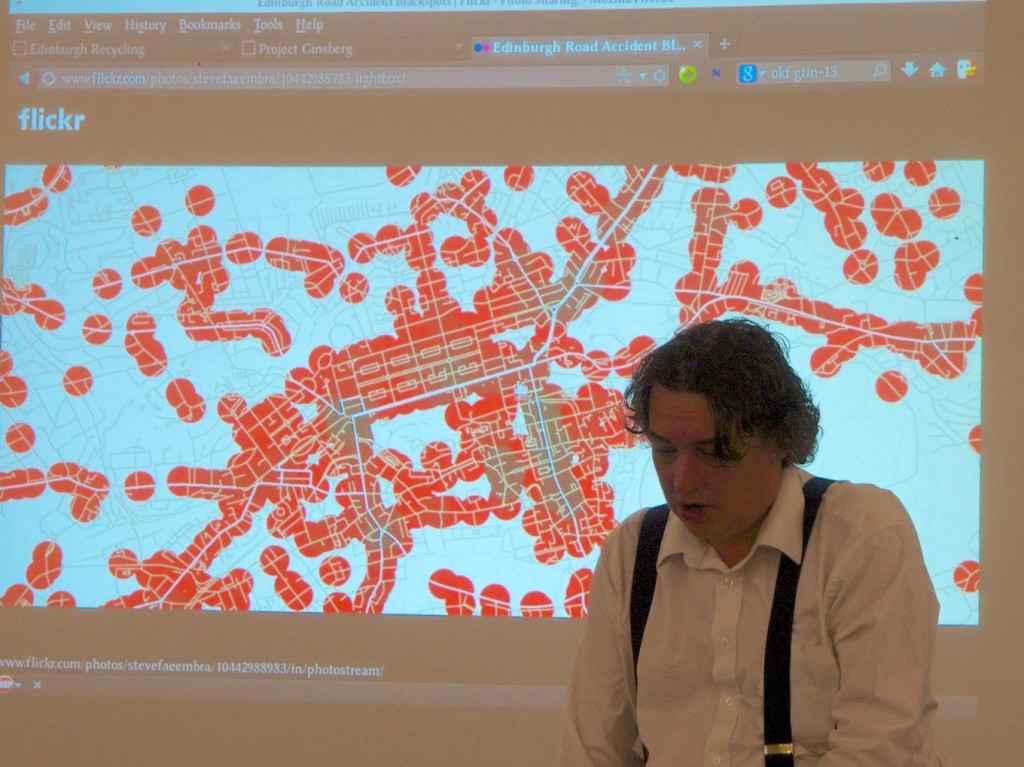

After demonstrating an heatmap of road accident data in Edinburgh made with QGIS over an OpenStreetMap base layer, similar to that presented by Clare Taylor, Steven Kay discussed Edinburgh Shop Local, an idea he had pitched at the Edinburgh Apps event.

The idea revolves around a ‘disloyalty card’ which promotes local businesses by encouraging shoppers to collect stamps from all participating local businesses. The Shop Local system would provide a portal where local shops could advertise their services and discounts, and would help people find out users where these shops are in their local area.

Steven also discussed a related website that highlights the location of empty shops in Edinburgh. Around 9% of shops in Edinburgh are vacant, with the figure rising to 30% in some areas. Mapping this data reveals how many empty shops are located in a ring around the city centre, and are bounded by out-of-town superstores. This could be invaluable as part of an urban asset audit, and perhaps a prelude to community driven initiatives for urban regeneration.

Mark your diaries: the next Edinburgh Open Data Meet-up will take place on January 22nd 2014 at the National Library of Scotland.